He was seventeen when he left home. He watched his father standing on the platform, waving sadly as the train rolled away. He would never see his father again.

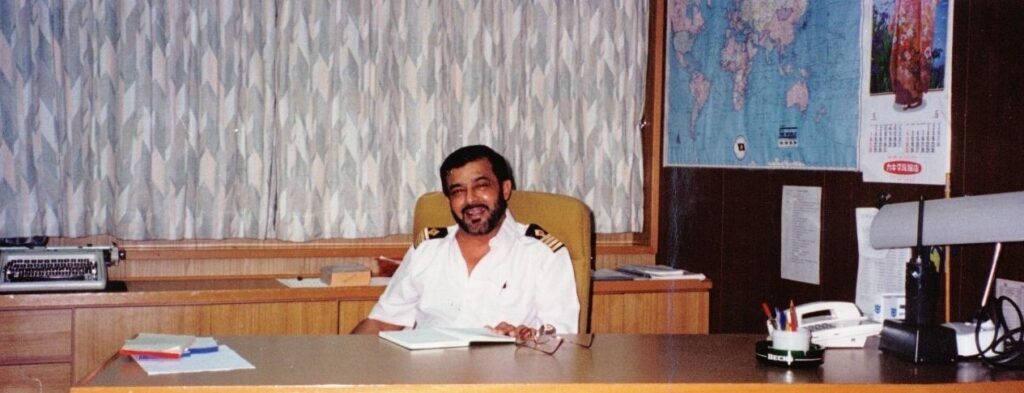

He went on to endure two years of grueling training followed by year-long apprenticeships on seagoing vessels. His career at sea spanned a little over thirty years. During that time, he commanded vessels of varying size, from general cargo ships to 270-meter long bulk carriers with a 152,000 DWT. He sailed through the Suez Canal, the Panama Canal, the Bermuda Triangle. He weathered storms at sea. He survived freak waves off Richards Bay. He discharged cargo over three months at outer anchorage off the coast of Luanda in war-torn Angola. He commanded supply ships off the coast of Bombay rushing supplies to oil rigs during stormy weather. He fought off pirates in the Strait of Malacca. He once climbed up the main mast in bad weather to change a lightbulb while his electrical officer and Boatswain watched from the deck as the swell caused the ship to corkscrew until the mast almost touched the giant waves. He performed life-saving surgery on one of his mates before rushing him to the nearest port for medical treatment. He oversaw a rescue mission for a suicidal officer who jumped into the Pacific off the coast of Hawaii. He navigated by the sun, the stars and charts when onboard navigation equipment failed in the Arabian Sea. He weathered a near mutiny in Brazil as brazen ship-owners delayed the payment of salaries to a crew of forty. He joined his crew in prayer on the main deck when nothing else could be done as they found themselves in the middle of a strengthening hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico. He escorted many a stowaway to safety and silenced officers who recommended tossing them overboard. He took a corrupt Chinese hiring agency to court in the port of Yanbu that helped dozens of expatriate day laborers get back their passports and return home. He oversaw sea burials.

In 1998, he gave it all up and moved to Iowa to be with his wife and son. She died a year later from Acute Myelogenous Leukemia. That broke him.

He drove a school bus and fought to be assigned to special ed. students. He said they were the best. He couldn’t stand being around junior high kids.

He drove a school bus until the doctors said his heart wouldn’t allow it. Then he spent more time in the garden. He did some Uber. Once he got a call from a Jehovah’s Witness priest who had a follow-up question about something they discussed during a ride. Another time, a young lady called him to thank him for picking her up in an inebriated state from a bar and for lecturing her all the way to her home about how her parents would be disappointed in her.

Then he gave up Uber. He spent more time in the garden.

On the 26th of August 2024, it took him almost twelve minutes to walk from the curb to the first rank at the mosque, typically a one-minute walk. But he still managed to get both cycles of the pre-dawn prayer. He died later that day.

* * *

The next day, I was swiping through his whatsapp messages and returning calls. One message caught my attention, from a name I did not recognize. The chat transcript showed several messages. She introduced herself and wanted to talk. She paid her condolences. She said her own father worked as Second Mate with my father on a general cargo vessel. She said she had met my father on board a ship. She was seven at the time. She remembered how kind he had been to her. She came to think of him as a dear uncle.

She tracked him down four years ago. He told her that he had a copy of the Quran that her father had gifted to him. It had handwritten notes from her father in the margins. He sent her pictures of it. She kept in touch after that.

I thanked her and said we would visit her if we ever had the chance. Then she said she needed a favor. “Anything,” I said, expecting her to ask for the copy to be shipped to her, which I would have been happy to do. Instead, she said, “Now that your Dad is gone, would you continue to read from it?”

I said I would.